What is the journey to a million?

UCAS projects that by the end of the decade, we could see up to a million students apply for higher education (HE) across the full range of Level 4 and above opportunities. In collaboration with Unite Students and Knight Frank, we examine those projections in more detail below.

Introduction

UCAS projects that by the end of the decade, we could see up to a million students apply for higher education (HE) across the full range of Level 4 and above opportunities. This is a result of a growing population looking to progress through education and training.

This marks a significant growth in demand, and will present challenges and opportunities across the entire student lifecycle — from discovery and application, to enrolment, completion and employment.

Participation in higher education has significantly increased since the millennium, with much made of Tony Blair’s 50% target. In 1994, there were just over 400,000 applicants to higher education, with half a million exceeded for the first time in 2005. The Higher Education Initial Participation Ratexi measured participation of those aged under 30 at just under 43% in 2012. It passed 50% in 2017/18 and reached 50.7% in 2018/19. Following the inclusion of additional providers, participation reached 53.4% in 2019/20.

The pandemic further accelerated demand for higher education. Driven by the economic climate, growing 18-year-old demographic, and inspiring efforts of frontline workers in sectors such as nursing, UCAS observed 60,000 additional applicants between 2019 and 2022xii .

Most recently, we have seen a slight decline in applicant numbers as of the January 2023 equal consideration deadline. In this complex cycle, impacted by cost of living and geopolitics, we remain confident this is a slight recalibration, particularly for those subjects that had seen extraordinary growth such as nursing. It remains our view that the trajectory for the remainder of the decade is growth, choice and competition.

The Journey to a Million is largely driven by an increasing 18-year-old population, with the ONS forecasting that there could be nearly 900,000 18-year-olds in the population in 2030 – an increase in 200,000 from 2020xiii. The Office for Students also shared a similar trend of growth in demand for HE, based on provider estimates and ONS estimation data. Providers’ forecasts suggest that between 2020 and 2025, there will be an increase of 70,000 FTEs (12.5%) in UK full-time undergraduate studyxiv. Furthermore, we expect the number of internationally mobile students to continue to grow — the OECD states that in 2000 there were 1.6m internationally mobile students, rising to 5.6m in 2020, and some forecast this could be as high as 8m in 2030.xv Finally, whilst the cohort is more variable, we expect continued demand from mature students to retrain and upskill, with initiatives such as the Lifelong Loan Entitlement (LLE) likely to change the pattern of adult education.

Furthermore, when looking at Key Stage 4 destination data, we see that over 570,000 students completed this phase of education in 2021.xvi Unsurprisingly, these figures have historically mirrored the 16-year-old population estimate. During this period, we have seen a decline in the proportion of students not having a sustained destination – from 9.2% in 2012, to 5.2% in 2021. In addition, when looking at the proportion of English students achieving Level 3 qualifications, this has increased 14 percentage points since 2006/2007, and has remained consistently above 60% since 2013/14.xvii In summary greater proportion of the cohort are progressing through Key Stage 4 to a sustained education or training destination.

Graph 1: ONS population projection of 18-year-oldsxviii

The Journey to a Million is far more than an increase in demand for education and training. The growth in higher education numbers has the potential to service the shifting status of the UK’s economy and its needs. The Working Futures 2017-2027 report, which looks at long-term labour market and skills projections for the UK, notes that the number of jobs in occupations which often require a high-level qualification is projected to continue to grow over the decade.xix The report sees this as reflective of the fact that in many occupations, jobs themselves are changing and will require higher qualifications. In addition to this, research from McKinsey suggests that we will see an increase in demand for skills which are traditionally taught at higher education institutions such as technological and higher cognitive skills, including critical thinking, decision making, and creativity.xx Automation and technological shifts will also see a decline in the need for work which uses physical, manual and basic cognitive skills. The projected increase in demand to higher education institutions can therefore support the need for high-skilled workers.

How have we arrived at the Journey to a Million projection?

As noted above, UCAS projects that there could be a million higher education applicants by the end of the decade, up from three-quarters of a million today. UCAS recognises that whilst we see an increase in the 18-year-old population, not all of these will progress to tertiary education. When projecting the potential volume of future student numbers seeking to enter higher education, we have taken the approach and applied assumptions listed below:

- We have collected data on the population sizes and growth trends for UK regions and nations, as well as internationally, using sources such as the Office for National Statistics and World Bank.

- We use other demographic information, such as age, to create hundreds of different applicant cohorts.

- Application rates from these cohorts are then projected using exponential smoothing, a forecasting method which uses a weighted sum of past observations (the weighting decreasing exponentially as an observation becomes less recent).

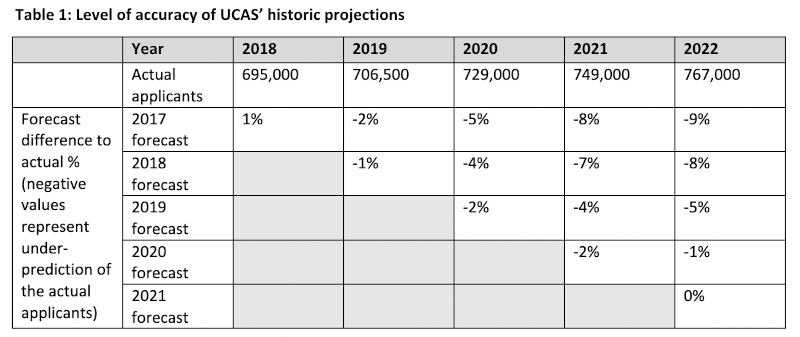

Despite the unpredictable effect of the pandemic on the number of applicants, this approach has produced forecasts which predict the number of applicants to within 10% of the true number five years following the date the prediction was made. We are observing an improvement in forecast accuracy for those projections made since the effect of the pandemic appeared in the time series. Furthermore, this trend in increasing demand is also reflected in increased participation with UCAS data showing an increase in acceptances of 5.4% from 2018 to 2021.xxi HESA data also mirrors this trend, where enrolments onto full-time undergraduate courses have increased by 10.4% from the 2018/19 to 2021/22 academic year (latest available data).xxii

How is the Journey to a Million made up?

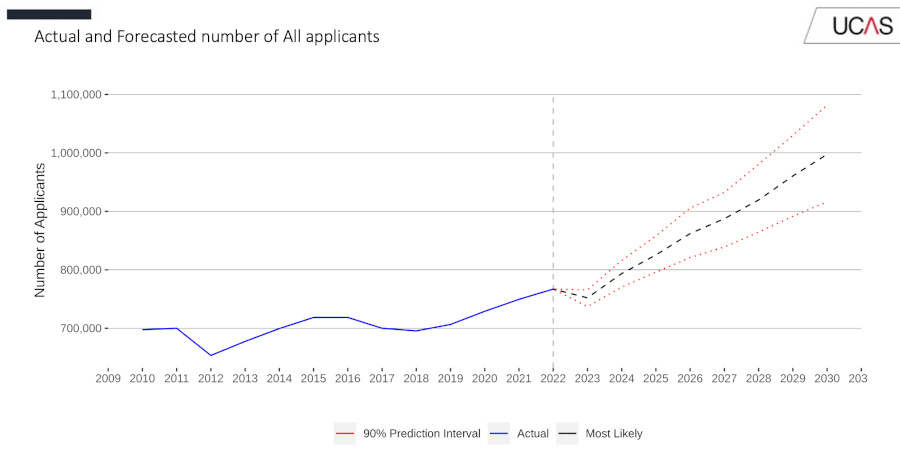

By 2030, there could be 30% more higher education applicants relative to 2022, with 90% prediction intervals projecting a range from an increase of 19.5% up to 41%.

Graph 2: Projected total number of higher education applicants up until 2030

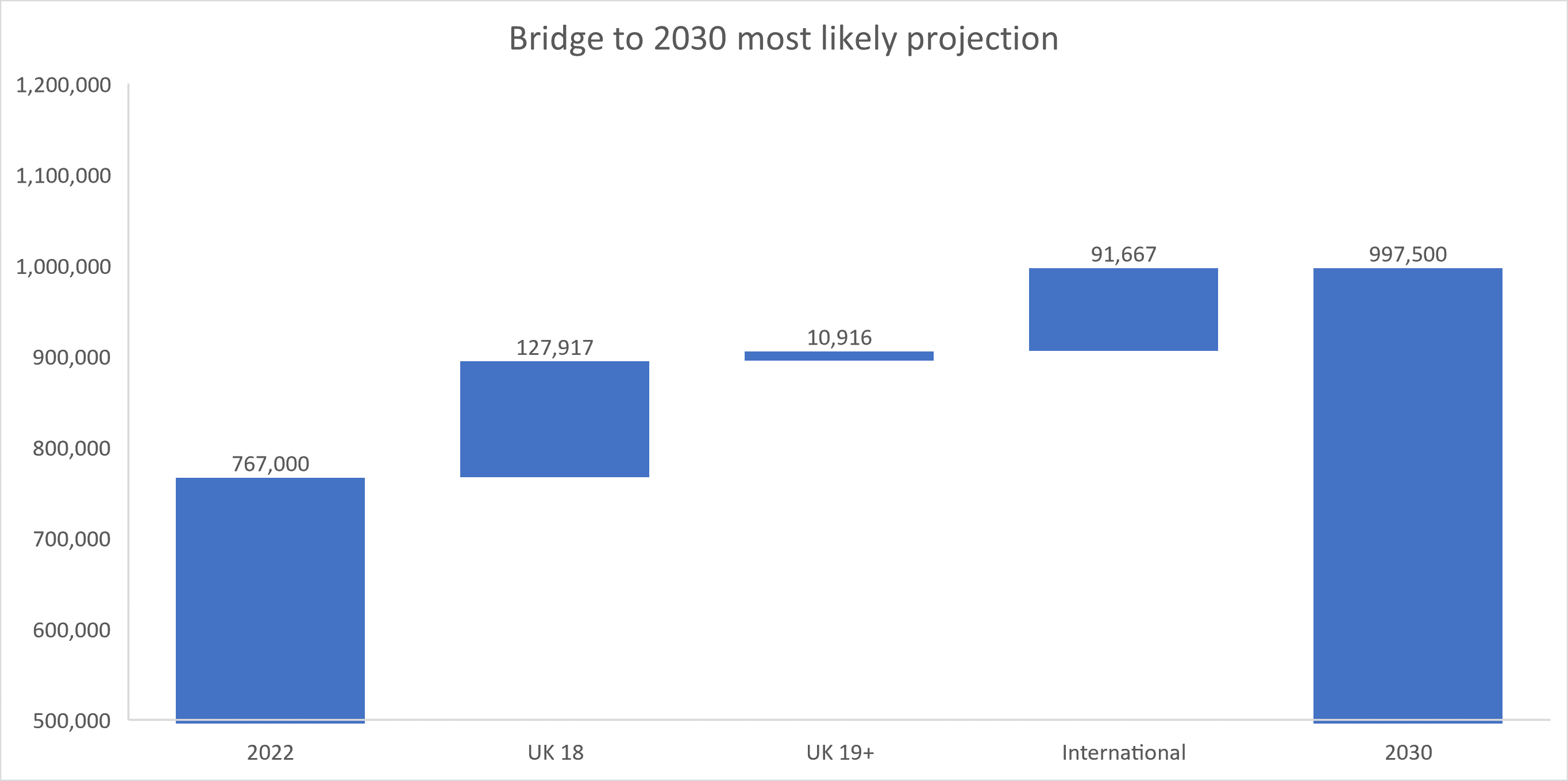

Graph 3: Bridge graph to 2030 ‘most likely’ projection

This growth is largely driven by an increase in the UK 18-year-old demographic, with a 38% increase in students from this background, which could see the total number of 18-year-old applicants increase to 457,000. Furthermore, we project that the number of 19-year-old applicants could grow to 101,000 (+10%).

Forecasting mature learners is more challenging due to the range of influences on their progression, including the wider economy and job market. At present, our most likely projection suggests mature student demand will remain flat, with our prediction intervals presenting both a decline and increase. However, given the introduction of the Lifelong Loan Entitlement in England, it is likely we will see changes in demand from mature students during this period.

We are also projecting a 75.6% increase in the number of non-EU applicants, which could bring the total number of applicants from outside the EU to close to 200,000. The number of applicants from the EU remains difficult to forecast given significant declines in recent years. However, the decline observed at the January 2023 equal consideration deadline was minimal (-320 compared to 2022), which could mean this trend is beginning to plateau.

UK domiciled students

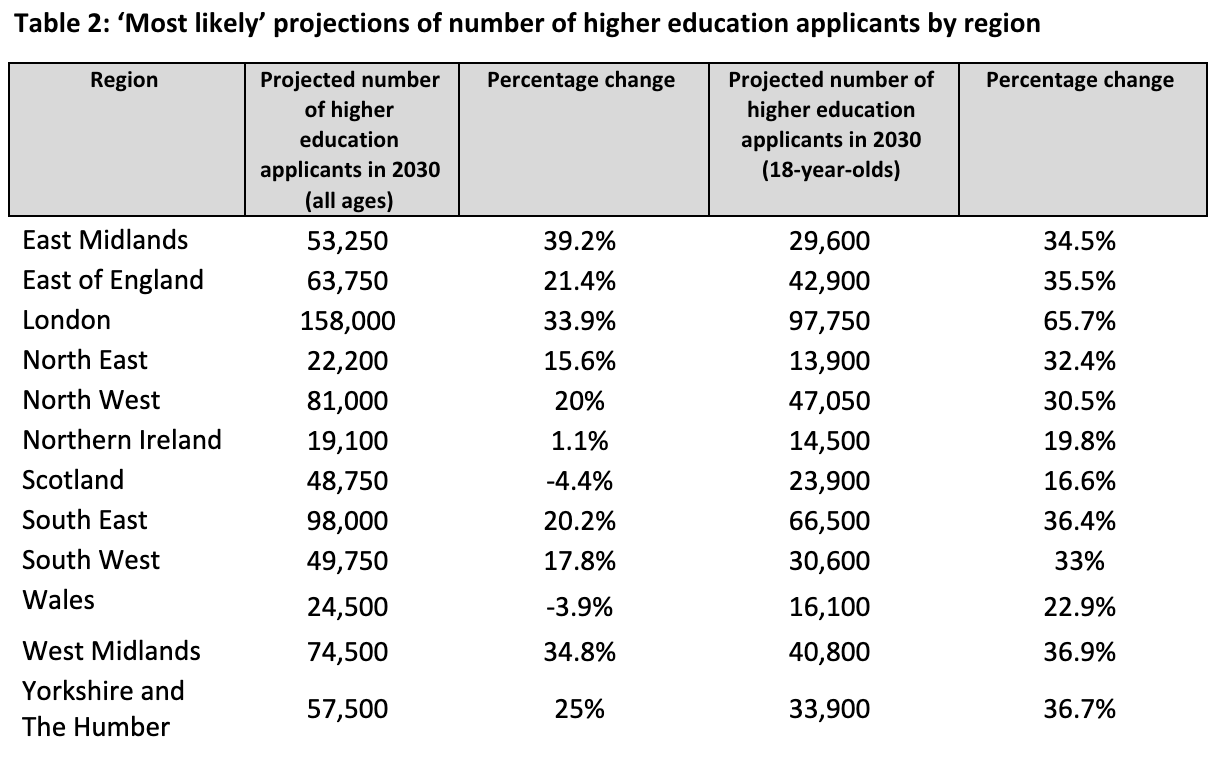

The Journey to a Million will see varying levels of growth across the UK:

- In England, we project that total domiciled applicants could grow by 26.8% (up to 659,500). Our prediction intervals suggest this increase could range from 15.3% to 38.4%

- In Scotland, we project that total domiciled applicants could decline by -4.4% (48,750)

- In Wales, we project that total domiciled applicants could decline by -3.9% (24,500)

- In Northern Ireland, we project that total domiciled applicants could grow by 1.1% (up to 19,100)

Within these headline figures, we also see significant variation by region. In recent history, London has had a significantly higher entry rate than other areas — with over half of 18-year-olds in London progressing to higher education, which is 20 percentage points higher than those from the North East and South West.

We project that this participation gap will continue. In London, we project that the total number of applicants from this region could increase by 33.9%, with the total number over 158,000. By contrast, we project that there could be a 15.6% increase in applicants from the North East (22,200 in total), and a 17.8% growth in applicants from the South West (49,750 in total), widening the regional disparity we currently see. The projected regional breakdown (using the ‘most likely’ projection), can be found below:

The variance seen by region, including declines in overall numbers, are for a number of reasons. These include the differences in population growth within these regions, the previously seen demand and proportion of mature students within the total applicants within this region. However, an increase in demand from 18-year-olds is observed across all regions.

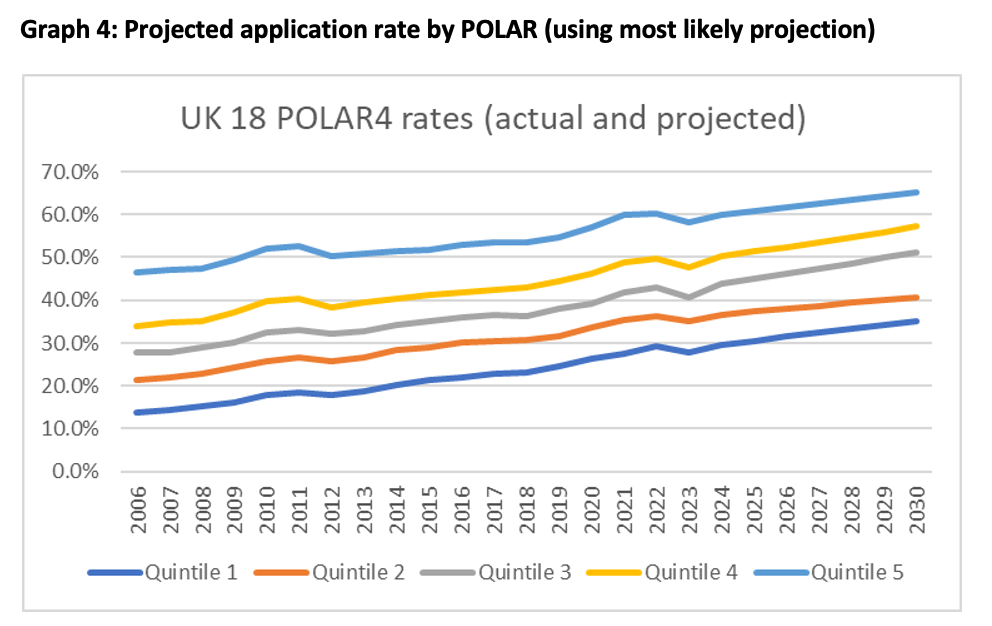

When looking at the background of these students, we expect to see growth across all POLAR4 quintiles. What we observe is that the application rate for Quintile 1 (those from the most disadvantaged backgrounds) students could reach 35%, an increase in 5.6 percentage points. For Quintile 5, we project an increase of 5.1%, suggesting we could see a narrowing of the application gap between the most and least advantaged. However, significant differences in engagement will continue to exist without targeted action – with the potential application rate for Quintile 5 students being 65.2%.

International students

We’re projecting an 60% increase in international students, signalling the ongoing attraction of UK HE. Within this, we see a 75.6% increase in higher education applicants from outside the EU, and slowing decline in EU students across the decade.

At the January 2023 equal consideration deadline, international demand continued to grow, with a +3.1% increase in applicants of all ages – this uplift was driven by countries such as Nigeria (+23.1%), India (+5.4%) and the United States (+9.8%). Applications from China declined (-4.2%), most likely due to Covid-19 restrictions and disrupted learning.xxiii

We project that China will continue to be the largest non-UK market for UK HE. Since 2020 more higher education applicants have applied from China than two UK countries, namely, Wales and Northern Ireland.xxiv 2030 could see applicant numbers exceed 50,000, more than the number of Scottish domiciled applicants for UK HE. This will see the UK remain heavily dependent on Chinese applicants, which as UCAS has previously commented, heightens the need for diversification to maintain the sustainability of the UK’s international recruitment market.xxv

Elsewhere, the trajectory for Indian applicants (an International Education Strategy [IES] priority country) continues, with demand in five years’ time set to reach around 40,000.xxvi The picture is less clear for Hong Kong, currently the fourth biggest market, where demand is set to plateau at around 6,000. Of additional note among the IES priority countries is Saudi Arabia, with demand set to reach 7,000, and of those markets referenced within the International Strategy for Wales, appetite from Irish students for UK HE is set to continue to grow, reaching nearly 6,000.xxvii

Whilst UCAS predicts this increase in international students applying to the UK, and other commentators have predicted significant growth in the volume of internationally mobile students, the remainder of the decade is likely to see a growing intensity in global competition. In 2000, the UK had the second largest market share at 14%, behind the US at 28%. Whilst the UK has maintained this position, market share had declined to 10% in 2020, with Canada, Australia and China all growing during this period.xxviii Therefore, whilst growth is forecast, this will be against a strengthening global market that is opening up borders following the pandemic.

What could disrupt the Million?

As with all projections, there are likely to be events that both positively and negatively impact on the trajectory seen, but also impact on the pattern of provision students progress to.

The advent and growth of T levels, Higher Technical Qualifications and Degree Apprenticeships has created a stronger and more linear technical education progression route that will continue to mature over the decade. At present, we know that interest in these opportunities is high — with nearly half of students interested in undergraduate opportunities also interested in apprenticeships. As this interest grows, we could see a greater proportion of young and mature students opt for this pathway over a three-year undergraduate pathway. Whilst this could still result in an overall increase of the number of students in higher education, the pattern of provision will be different, but still contribute to the projected growth.

Furthermore, with the roll out of the Lifelong Loan Entitlement promoting a ‘bite-sized’ form of higher education, and strengthening the appeal to adult learners, we could see a reduced number of students enter higher education at 18, instead preferring a more ‘real time’ experience as they progress through their career, reducing the 18-year-old entry rate, but increasing mature participation. Furthermore, the LLE would potentially broaden the range of individuals engaged with education, increasing mature student numbers.

As we have observed in recent history, demand for higher education can be influenced by a range of factors, including the state of the economy, geopolitics and policy change. The impact of these can be prolonged or immediate depending on the event, with the most obvious example being the pandemic, which led to a significant growth in nursing applicants.

For the purpose of the Journey to a Million, we have identified five key disruptors that could impact on the overall demand for higher education. These include:

1. Significant change to the pipeline of international students entering higher education:

Whilst the UK has experienced growth in international student numbers over the last decade, this market is more volatile than the domestic market. The UK has largely been reliant on China for the recent growth — with 2 in 9 international students accepted from China, and China now established as the third largest market for UK HE.xxix

Furthermore, the UK’s reliance on a small number of nations, with seven nations providing half of the UK’s undergraduate applicants, means that events in specific countries could disrupt these projects. For example, some commentators have suggested the UK may be close to ‘peak China’xxx, which would impact on the overall trajectory of international student recruitment.

Geopolitics has a large influence on international student progression, as does global competition. Growing global tensions could have a rapid impact on the progression of international students from specific nations — as we have seen following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Furthermore, as nations begin to open their borders following the pandemic, nations across the globe will be seeking to attract these students, potentially reducing the UK’s market share — with Australia’s extension of post-study work visas for certain courses a clear strategic move to attract and retain more international students.xxxi

In consideration of this, we have modelled:

- A significant and sudden drop in international applicant numbers due to a specific geopolitical event

- A reduction in UK market share to 8%

- An increase of UK mature share to 2000 levels (14%)

2. Significant shift in higher education policy that restricts growth:

Government policy in relation to funding of provision can significantly impact on student choice. For example, approaches to the management of student numbers vary across the UK. Whilst England and Wales broadly allow for unrestricted recruitment across most courses, Scotland and Northern Ireland have number control policies in place for ‘Home’ students. It was the changes to number controls and the establishment of an open market that has facilitated significant expansion of higher education since 2012, with nearly 100,000 additional applicants since this point.xxxii

The current projections within this report assume that UK-wide number controls do not return. However, some form of number controls were considered in England as recently February 2022.xxxiii Their reintroduction would likely curtail continued expansion of higher education provision, and therefore impact applicant numbers.

In consideration of this, we have modelled:

- A significantly reduced growth in the 18-year-old application rate

3. Demand for higher education hits a natural of ceiling, with no increase in the participation rate:

Higher education participation has continued to grow since the millennium, with much made of Tony Blair’s ambition to reach a 50% participation rate. The Higher Education Initial Participation (HEIP) methodology has estimated that HE participation has exceeded this target since the 2015/16 academic year.xxxiv Similarly, the UK entry rate — a key measure of demand for higher education - has grown nearly 9 percentage points since 2013 to 37.5%.xxxv

However, it cannot be assumed this growth will continue exponentially. In 2020/21, 62.2% of students 19 and under in England had achieved Level 3 qualifications, compared to 59.1% in 2012/13.xxxvi Growth in this area has been slower than the growth in HE participation, and we may see a plateau in the overall higher education participation rate as a result. However, this would still result an increase in the total number of students applying to higher education given population increases.

In consideration of this, we have modelled:

- A flat application rate

- A significantly reduced growth in the 18-year-old application rate

4. Economic boom period, or buoyant job market, leading to a reduced demand for higher education from mature students:

Ordinarily, in a period of economic downturn, the demand for higher education from mature students increases, particularly if the job market is less positive. For example, from 2008 to 2012, when job vacancies were at a low point, we observed an increase in the 21–50-year-old application rate. However, when job vacancies started to increase from 2013, the application rate declined.

With an economic downturn widely forecast in 2023, should the UK emerge from this strongly, it is likely to have a negative impact on mature participation, as these individuals opt to enter the job market.

In consideration of this, we have modelled:

- A 10% decline in demand from mature applicants

5. Prolonged recession with a worsening job market, leading to increased demand for higher education from mature students:

As noted above, the state of the economy impacts on mature student participation. Therefore, should the forecast recession in 2023 be sustained and harsh, this could have a positive impact on mature participation. However, it should be noted that, at present, mature participation continues to decline despite uncertain economic conditions. It is our belief this is due to the high number of job vacancies currently available.

In consideration of this, we have modelled:

- A 10% increase in demand from mature applicants

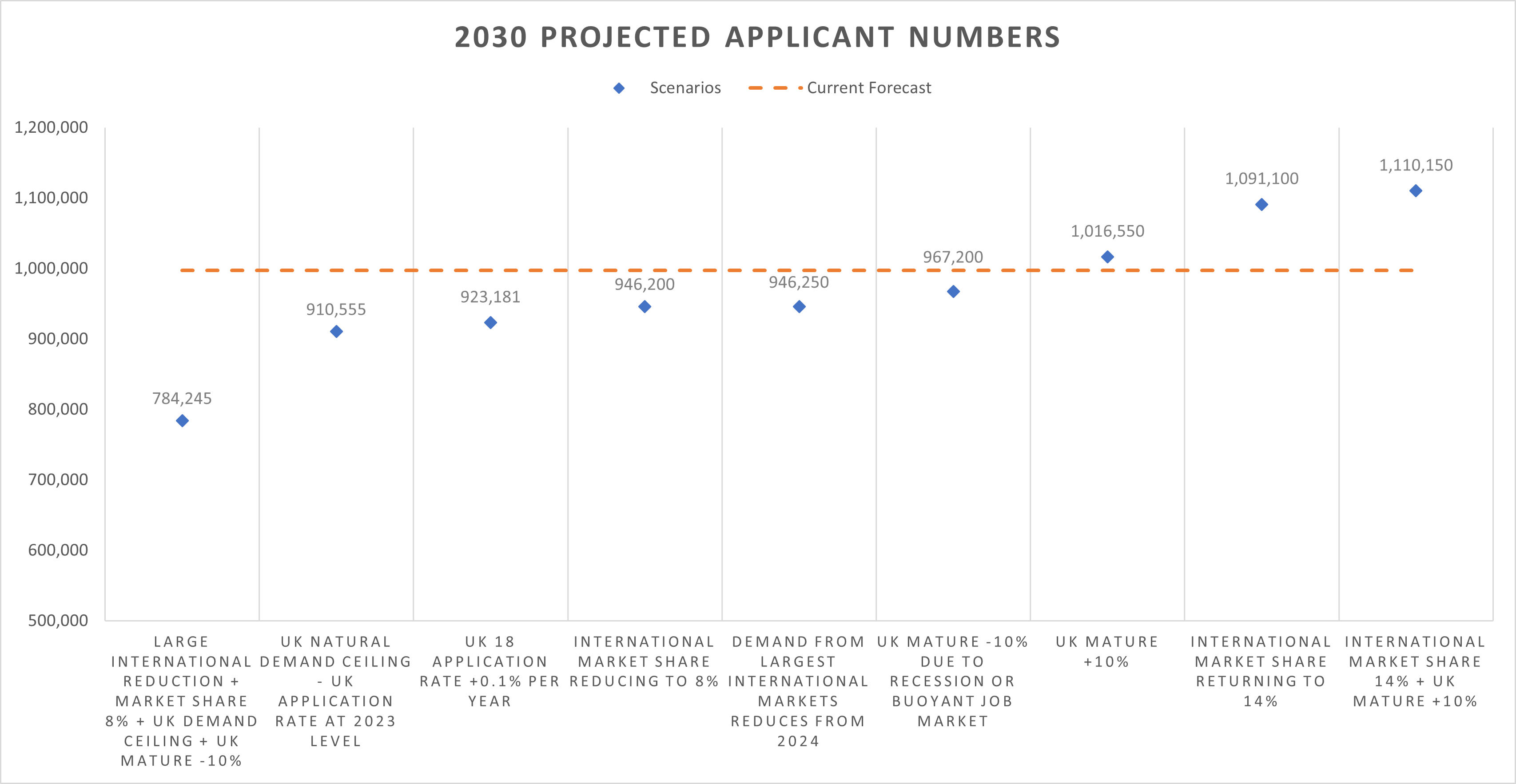

UCAS has modelled the impact of these scenarios on the overall demand for higher education, including what occurs should we see multiple events. It is UCAS’ view that, in the event of any single significant disruption outlined above, we continue to project 911,000 higher education applicants – which remains a significant growth on numbers currently seen. Furthermore, some disruptors could result in further accelerated demand, with numbers reaching almost 1.1 million. Our most pessimistic, and unlikely, scenario – with multiple events occurring - projects that we only reach 784,000 applicants, with all cohorts seeing reduced or stagnant demand.

Graph 5: Impact of disruption to Journey to a Million projections (using ‘most likely’ projection)

Data files

Footnotes

xi The Department for Education (DfE) publishes annual participation rates for England. The Higher Education Initial Participation Rate19 (HEIPR) was first produced to measure progress against the last Labour Government’s 50% higher education aspiration. This measure covers 17–30-year-old English domiciled first-time participants in HE at UK HE Institutions, and at English, Welsh and Scottish Further Education Colleges. The HEIPR is a sum of the participation rates for each age from 17 to 30 inclusive, or each age from 17 to 30. A new methodology was introduced in 2006/07. Department for Education (January 2023), Participation measures in higher education.

xii UCAS (2022), Next Steps: Who are the ‘future nurses’?

xiii Office for National Statistics (2019), National population projections: 2018-based.

xiv Office for Students (2022), Financial sustainability of higher education providers in England.

xv OECD (2020), Education at a Glance 2020: What is the profile of internationally mobile students?

xvi Department for Education (October 2022), Key stage 4 destination measures.

xvii Department for Education, Level 2 and 3 attainment age 16 to 25, Academic year 2020/21.

xviiiThe population estimates are based on Office for National Statistics mid-year estimates, and national population projections (published in 2018 and based on the 2011 census). For 18-year-olds, the estimates are obtained by ageing 15-year-olds from the appropriate number of years earlier. This approach avoids the estimates being susceptible to changes in net migration (including overseas students) as this age. The estimates are adjusted from age at mid-year to age on the country-specific reference dates, using the monthly distribution of births. Office for National Statistics (2019), National population projections: 2018-based.

xx McKinsey (2018), Skill shift: Automation and the future of the workforce.

xxi UCAS (2022), Undergraduate End of Cycle Data Resources 2022.

xxii HESA (January 2023), Who’s studying in HE?

xxiii UCAS (2023), 2023 Cycle Applicant Figures – 25 January Deadline.

xxiv UCAS (2022), Where Next? What influences the choices international students make?

xxv Ibid.

xxvii Welsh Government (2020), International strategy.

xxviii Project Atlas (2020), Global Mobility Trends.

xxix UCAS (2022), Where Next? What influences the choices international students make?

xxx Maddaline Ansell (November 2022), A truly global Britain needs more people with a global outlook.

xxxi Grace McCabe (February 2023), Australia adds two years to post-study work visa.

xxxii UCAS (2022), Undergraduate End of Cycle Data Resources 2022.

xxxiii Department for Education (2022), Higher education policy statement and reform.

xxxiv Department for Education (January 2023), Participation measures in higher education.

xxxv UCAS (2022), Undergraduate End of Cycle Data Resources 2022.

xxxvi Department for Education (April 2022), Level 2 and 3 attainment age 16 to 25.

In collaboration with: